THE MONACO GRAND PRIX LIBRARY BY ROY HULSBERGEN THE MONACO GRAND PRIX LIBRARY BY ROY HULSBERGEN |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

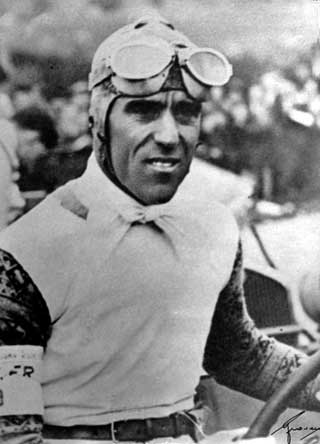

Tazio Nuvolari |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Born in Castel d'Ario, Italy on November 16, 1892 Racing Career

Tazio Nuvolari became a legend in his lifetime. There is no end to the almost incredible, but true stories told about this thin little man, no more than 1.65m tall, who for almost 25 years, remained at the top of the hierarchy and displayed almost incredible courage in adversity. Dr Ferdinand Porsche called Nuvolari "The greatest driver of the past, the present, and the future.". His indomitable courage sent him several times to hospital. In 1936, he had a serious accident during practice for the Tripoli GP and was again sent to hospital, but managed to defeat the doctors’ vigilance, took a taxi to the circuit and, all bandaged and a leg in plaster, got into a spare car and finished seventh! On another occasion, just after the war, he drove a little Cisitalia when the steering wheel came off and managed to reach the pits holding the wheel in one hand and the steering column with the other to steer the car! In 1947, though seriously ill from the cancer from which he was to die six years later, he led all the big hands in the Mille Miglia - 1000 miles from Brescia to Rome and back, crossing the Appenine twice - all the way, in a tiny open 1100cc Cisitalia in pouring rain. Then, only 150km from the finish, the rain played havoc with the ignition, which let Biondetti with his big, closed Alfa through to win. Nuvolari still managed to get home second, but he had been the hero of the race. No wonder he became a legend in his lifetime ! Nuvolari did not begin to race cars before 1924, when he was 32, after a very successful career as a racing motorcyclist, he won almost every race worth winning at least once, starting as a private entrant with a Bugatti and becoming an official Alfa-Romeo driver in 1929. His most successful year was surely 1933 when he won the Mille Miglia, the Tunis GP, the Le Mans 24 hours Race, the Eifelrennen and the races in Nimes and Alessandria, all on Alfas, the Belgian GP, the Spanish GP, the Copa Acerbo, the Coppa Ciano and the Nice GP, all on Maserati, and the Ulster Tourist Trophy driving an MG Magnette. That was the year when he fell out with Ferrari who managed the Alfa team, and for the Belgian GP he entered a 3- litre Maserati. In practice, he found that the car was very fast, but needed all the width of the road on the very fast straight to Stavelot on the Spa circuit. So he immediately sent the car to the Imperia car factory near Liège to have the chassis frame stiffened ... and on the Sunday, he won the race, beating Mr. Ferrari’s Alfas! Once the German cars had found reliability - in the second half of 1934 - the Alfas, Maseratis and Bugattis could win only the lesser races for which the Germans did not enter. Except if Nuvolari was at the wheel and the course was a “driver’s circuit”. If there ever was one, it is the Nürburgring on which the German Grand Prix was traditionally staged. As the Tipo B Alfas were completely outclassed, Ferrari lured Nuvolari back into his Scuderia. He was his only hope. And he was entered for the race which was expected by the Nazi leaders to turn into a public demonstration of German superiority. But Nuvolari thought otherwise. For 500km, so long were the Grand’s Prix at the time, he drove like a maniac, leaving all the German cars and drivers behind except one: von Brauchitsch, in his flamboyant style, had managed to stay ahead. But his spectacular power slides had been just too much for his tyres and, on the 22nd and last lap, one of them burst at the Karusell and Nuvolari went through to win. And Giovinezza was played instead of Deutschland über Alles... Though new models were produced, the Alfas never caught up with the Germans and by 1938, Nuvolari was fed up with getting beaten. In the opposite camp, Auto Union had lost their star driver, Bernd Rosemeyer, who had been killed in a record attempt. The Auto Unions were notoriously difficult to drive and only Rosemeyer could make them competitive. Their only chance was Nuvolari who was only too happy to accept the German’s offer. As expected, it did not take him long to understand the mid-engine car with which he won the British and the Czechoslovakian Grand’s Prix. When peace was re-established, Nuvolari was 53, but did not think a minute of quietly retiring. Alfa Romeo who now had the best cars, considered him to be too old to be taken into the team. So he chose to drive privately entered Maseratis and Ferraris and won two more races in Albi and Parma. After his heroic drive in the 1947 Mille Miglia, he again tried his hand at the most famous of all Italian races one year later, but illness and exhaustion forced him to retire. Motor racing was incomparably more dangerous at Nuvolari’s time than to-day and year after year, death struck the racing∞ fraternity several times. No driver ever took more risks than did “il Mantovano volante”, but his destiny was to die quietly in his mantuan home, surrounded by his family. Legacy

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||